Mary McKillip and Danielle Farrie

Abstract

Teachers in Georgia’s public schools are unhappy about low pay and poor working conditions impacting their ability to provide a quality education to all students. A qualified teaching staff is an essential resource needed to give students a meaningful opportunity to succeed in school. Despite recent funding increases, Georgia districts are hiring new teachers without standard certification at higher rates, and more inexperienced teachers are in classrooms now than six years ago. Teachers are leaving the Georgia public schools altogether or switching to different districts in the state. Georgia’s majority Black and low-income school districts are struggling much more than other districts to hire and retain experienced teachers with standard certifications. Lawmakers must make a stable workforce of qualified teachers across the state a top priority on their public education legislative agenda. Increased funding can be targeted to teacher salaries and better benefits, teacher hiring and development, and improved school climate and school resource allocation to attract and retain quality teachers.

Report PDF | Press Release | Interactive Tools

Introduction

Teachers in Georgia’s public schools are unhappy about low pay and poor working conditions impacting their ability to provide a quality education to all students, and they are letting their grievances be known. Teacher complaints and protests helped secure a $3,000 salary increase in the 2020 state budget, a partial fulfillment of Governor Kemp’s campaign promise to raise teacher salaries by $5,000.[1] This salary increase follows an initial raise under the state’s school funding formula in 2019, which reversed a decade of deep austerity cuts to education funding made by the Legislature in the wake of the 2008 recession.

Georgia has the 6th largest teacher gap in the nation. Teachers make 73 cents for every dollar earned by similar non-teaching professionals.

But an important question remains: do Georgia school districts have the funding necessary to attract, support and retain a qualified teacher workforce? This report attempts to shed light on this crucial question. Our findings show that, despite recent funding increases, Georgia’s majority Black and low-income school districts are still struggling to hire and keep experienced and certified teachers in their classrooms.

Research demonstrates that a qualified teaching staff is an essential resource needed to give students a meaningful opportunity to succeed in school.[2]A state public education finance system must provide sufficient funding for all districts to attract and retain a high-quality teacher workforce and offer salaries and benefits competitive with other districts and schools and commensurate with the labor market in which the district operates.[3]

This report reviews staffing data from the Georgia Department of Education on certified teachers in school districts in the 2018-19 school year and, in some cases, compares that data to information from the prior school year or the 2012-13 school year.

We examined certification status, experience, and teacher stability statewide and by district type. District-specific differences can be viewed using the interactive tools.

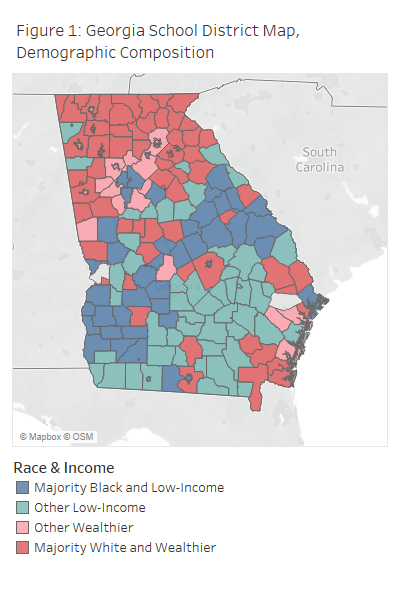

To examine variations in teacher characteristics by district race and poverty[4] composition, districts were grouped into four categories, as shown in Figure 1:

- Majority white and wealthier districts are those where over 50% of the students enrolled are white, and less than 40% of the students are low-income (68 districts);

- Other wealthier districts have a non-white majority or no majority race student population and less than 40% of students are low-income (18 districts);

- Majority Black and low-income districts have student populations in which over 50% are Black and over 40% are low-income (43 districts);

- Other low-income districts have a non-Black majority or no majority race student population and more than 40% of students are low-income (51 districts).

Qualified Teachers

Georgia school districts have lowered student-to-teacher ratios by hiring more teachers in recent years. Yet, our analysis shows this has not resulted in an increase in qualified teachers.[5] If newly hired teachers are less qualified and more inexperienced, the educational impact of a smaller class size may well be diluted.

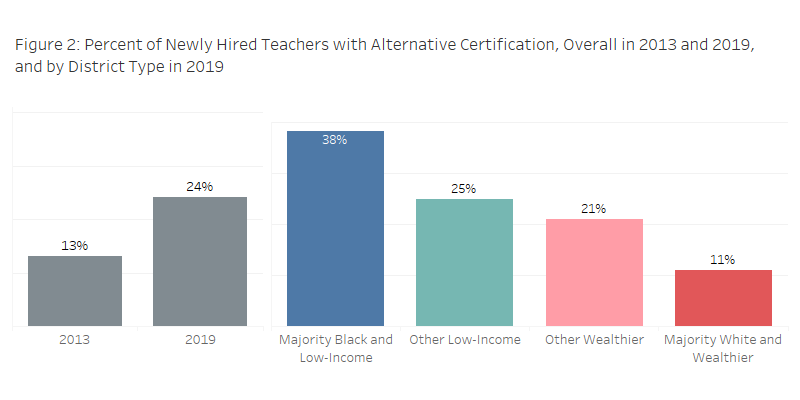

Georgia districts are increasingly hiring new teachers without standard certification. Nearly a quarter of newly hired teachers entered with an alternative certification[6] in 2019, while 13% of new hires had an alternative certification in 2013. This trend is more severe in majority Black and low-income districts. These districts are more likely to hire teachers with alternative certification – particularly when compared with majority white and wealthier districts. Among new teachers hired in the majority Black and low-income districts, 38% had an alternative form of certification in 2019, compared to just 11% of new teacher hires in majority white, wealthier districts.

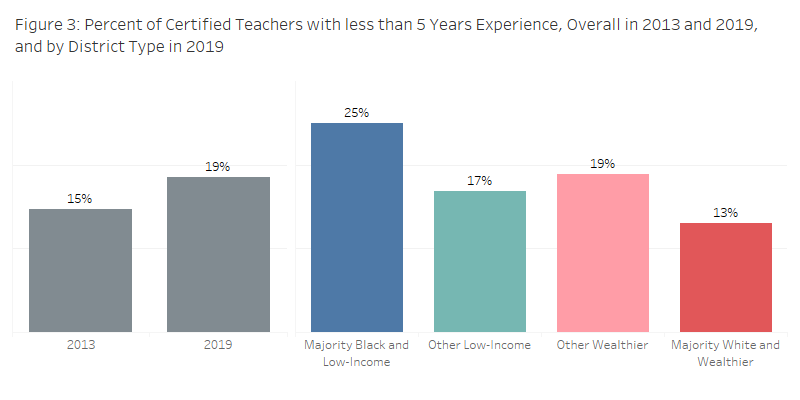

The data also shows that, statewide, the proportion of teachers with five years or less experience has increased, from 15% in 2013, to 19% in 2019. Majority Black and low-income districts have higher concentrations of these less experienced teachers (25% in 2019) than majority white and wealthier districts, where just 13% of teachers had less than five years of experience in the classroom.

For district-level visualizations of the analyses in this report, view our interactive tools.

These findings suggest that majority Black and low-income districts must make compensatory decisions because of limited funding, opting for smaller class sizes with less experienced teachers instead of larger classes with fewer but more experienced teachers. This choice may also be compelled by teacher labor market forces, since qualified, experienced teachers may be in short supply and less inclined to take on the challenge of a large class with struggling, at-risk students.

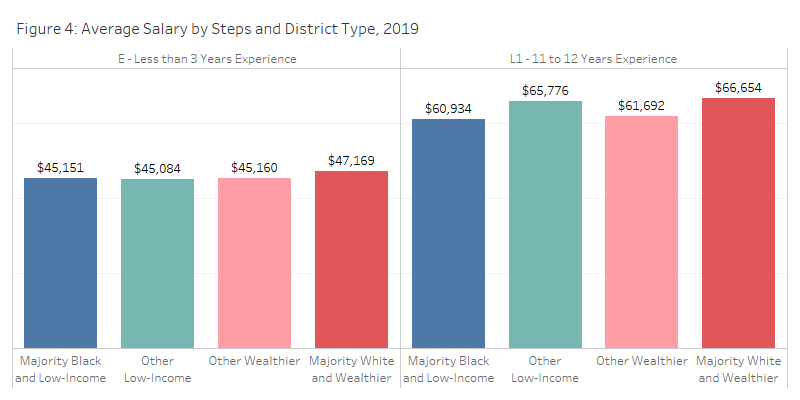

As would be expected, teachers with standard certification and more years of experience have higher salaries (See Box below). As the data in the chart below shows, a teacher at step ‘E’ with less than three years of experience teaching has a significantly lower salary than a teacher at step ‘L1’ with 11 or 12 years of experience. When examining teacher salary data by district type, the average pay for new teachers, after adjusting for wage differences due to district location, is comparable across district types, with a slight benefit for teachers in the majority white and wealthier districts. While majority Black and low-income districts are offering new teachers comparable salaries, these districts struggle to retain them, as the data in the next section shows.

Certification and years of experience are imperfect measures of teacher quality.[7] Yet, Georgia’s increase in new teacher hires with alternative certification and the decline in teachers with more years of experience are a troubling trend, especially in majority Black and low-income districts.

Understanding Teacher Pay and School Funding in Georgia

Georgia teachers are paid a minimum salary determined by the state’s salary schedule. Salaries increase according to years of experience, education level and certification type. For the 2019-20 school year, the base salary for a teacher with 0-2 years of experience, a bachelor’s degree and standard certification was set at $37,092.

While this schedule sets the minimum that teachers must be paid, school districts may use a local salary schedule to supplement the state minimums. These local supplements may be in enacted in response to differences in supply and demand, regional cost of living differences, or the value that local districts place on experience and education levels.

The ability of districts to supplement the state salary schedule is related to how Georgia funds its school districts. Georgia’s state funding formula, the Quality Basic Education Act (QBE), calculates state aid to districts largely based on the cost of staffing programs. The QBE calculation is based on student enrollments and established student to teacher ratios. Adjustments are made to account for the “training and experience” of teachers already employed by the district, or the salary districts pay above the base in accordance with the state salary schedule.. These are called direct instructional costs. A second formula determines non-instructional costs, such as administrative and facilities costs.

School districts are required to contribute a “local fair share” to support a portion of these total costs, which is based on the ability to raise revenue locally by levying a set property tax rate (5 Mills or $5 for every $1,000 of property value). The state provides the remainder, though austerity cuts in the last decade have reduced the state’s contribution below the levels required. In 2018-19, the state’s portion of the formula was fully funded for the first time since the 2008 Recession.

Many districts raise local revenue above the local fair share in part to supplement the state salary schedule. Because a district’s ability to raise additional revenue varies by property wealth, Georgia provides Equalization Grants, which supplement low-wealth districts so their tax efforts are equal to that of the wealthiest districts in the state. However, the target for these grants has decreased steadily from the 90th percentile to the state average in recent years, reducing both the size of the grants and the number of eligible districts.

While the QBE in theory takes steps to put districts on an equal playing field to raise revenue and thus provide competitive salaries to attract and retain teachers, formula underfunding undermines that goal. Moreover, fundamental flaws in the formula itself, such as not providing additional resources to address student poverty, disadvantage low-income districts’ ability to staff their schools at levels appropriate to meet the needs of their students by providing, for example, smaller class sizes, supplementary instruction and instructional coaches.

Teacher Workforce Stability

As teachers gain skill through experience in the classroom, students benefit.[8] When teachers leave the teaching profession early or transfer to other districts, students in the districts that made the initial investment in their training and support lose the benefit of these individuals’ pedagogical knowledge, classroom management skills, and ability to coach and mentor new hires.

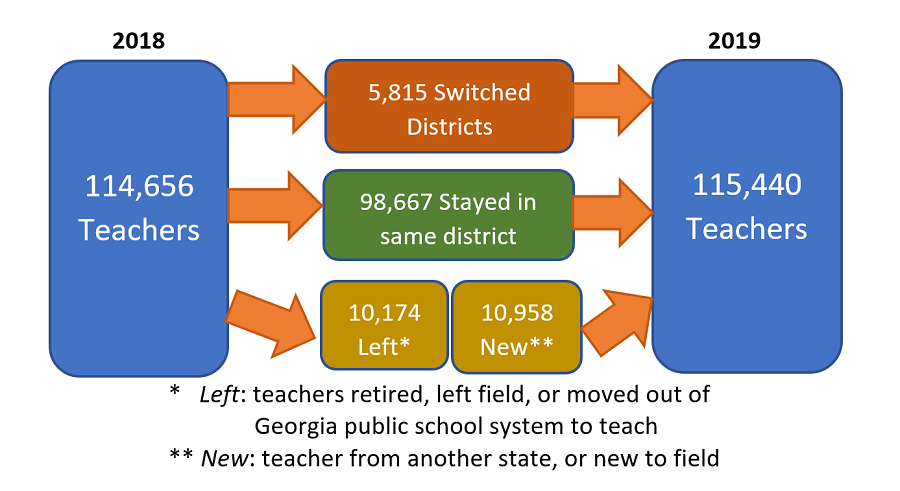

What does the data show about the stability of Georgia’s teacher workforce, that is, retention of teachers in their districts from year to year? Although there were more certified teachers in Georgia school districts to start the 2018-2019 school year than in the year prior (115,440 compared to 114,656), approximately 16,000 teachers left their districts between the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 school years. Over 10,000 of those teachers left public school teaching altogether, while nearly 6,000 switched from one Georgia district to another. Teachers who exit the profession are more likely to either be at the end of their careers (retiring) or in the early years of their career and have alternative certification.

Figure 5: District Teacher Turnover, 2017-18 to 2018-19

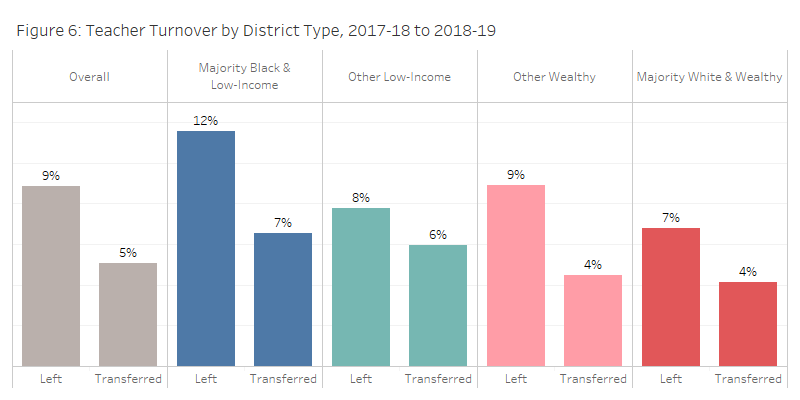

The teacher workforce in majority Black, low-income districts is more unstable. Data shows that from the 2017-18 to 2018-19 school years, 5% of teachers, or 5,815 people, switched districts statewide compared to 7% in majority Black, low-income districts. While 9% of teachers left school districts overall (10,174), 12% left majority Black and low-income districts at the end of the 2017-18 school year.

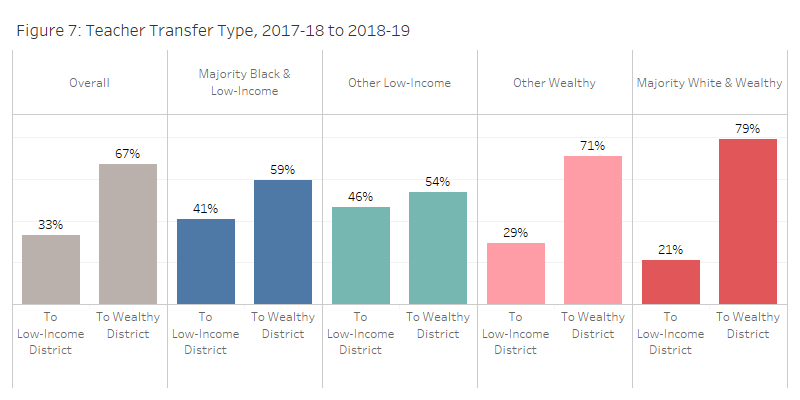

The data also shows that teachers who transferred to districts within Georgia were more likely to move to a majority white, wealthy district. As Figure 7 shows, although teachers coming from low-income districts are less likely than teachers coming from wealthy districts to switch to a wealthy district (59% and 54% from low-income to wealthy, compared to 71% and 79% from wealthy to wealthy), the majority of teachers from all district types transfer to wealthy districts. In 2019, 33% of teacher transfers moved to a low-income district, while the remaining 67% of teachers transferred to a wealthy district. This means that new hires in wealthy districts are more likely to have classroom experience, while majority Black, low-income districts cope with a greater “churn” of new, inexperienced teachers each year.

It is estimated that teacher loss or “attrition” can cost a district 30% of the departing teacher’s salary.[9] Using this estimate, along with Georgia’s average teacher salary of $57,000 in 2019, the average cost of a teacher leaving a district is approximately $17,000. These costs will vary by district type as well as the teacher’s experience level when hired, and include school and district expenses related to teacher separation, recruitment, hiring, and training.[10] Thus, majority Black, low-income districts incur increased costs from having to hire new, inexperienced teachers just to keep pace with those transferring out or leaving the profession altogether.

Recommendations for Improving Georgia’s Teacher Workforce

Our analysis shows that experienced teachers with standard certification have higher salaries and are more likely to work in majority white, wealthier districts. In sharp contrast, new teachers with alternative certification have the lowest salaries and are more likely to work in majority Black, low-income districts. Furthermore, Georgia’s teacher turnover levels are significant, particularly in majority Black, low-income districts whose students would greatly benefit from a more experienced and qualified teacher workforce.

One of the most crucial resources for Georgia public school students to have a meaningful opportunity for success is a qualified and experienced teacher in every classroom. As this report shows, lawmakers should make a stable workforce of qualified teachers across the state a top priority on their public education legislative agenda.

For additional information on teacher workforce research and policy suggestions, see

“Solving the Teacher Shortage: How to Attract and Retain Excellent Educators.”

Adequate funding is the essential building block to advance this goal. Increased funding to raise teacher salaries and improve working conditions, particularly in racially isolated districts serving high concentrations of low-income students, is a pivotal first step.

Research has identified four key strategies to improve the teacher workforce:

- Increase Teacher Salaries and Benefits, Overall and Targeted Consistent increases in teacher salaries are key to advancing workforce quality and stability.[11] There are three basic elements to this strategy: offering a base salary competitive with other comparable professions, providing additional pay and benefits to teachers working in high need schools, and boosting salaries targeted to “master” teachers or those with deep skill and experience.

- Focus on Hiring and Development Policies designed to support, mentor and train newly hired teachers are crucial to workforce development.[12] Teacher coaching, for example, has shown to be successful in fostering the skill of new teachers or those with less experience.[13] Districts need targeted funding to undertake these supports, which are essential to attract and retain experienced, qualified teachers. Evidence suggests that the selection of teachers is also important.[14] Effective teachers display not only pedagogical and content knowledge but also strong student-teacher relationships that involve social and emotional competence and classroom management skills.[15] Ensuring that the state’s teacher preparation programs are adequately preparing future teachers in these areas is critical.

- Improve School Climate School. climate is also critical to teacher success. The quality of school leadership, school building conditions, school safety, class size, teacher-to-teacher support, guaranteed planning time, and professional development opportunities all impact whether a teacher chooses to stay in his or her current district placement or even stay in the field of teaching at all.[16] These factors are especially important in schools with high enrollments of struggling students and students academically at-risk.

- Improve resource allocation. Making teacher salaries more competitive is an essential but insufficient step in building Georgia’s qualified teacher workforce. At a minimum, all Georgia districts must have the education resources necessary to ensure schools are safe, have reasonable class sizes, offer a rich and rigorous curriculum, and have academic and non-academic supports for students, such as tutoring, guidance counselors, social workers and nurses.

In a recent report on Georgia’s school funding formula, we strongly recommended the Legislature commission an independent cost study to identify, define and determine the essential education resources needed by Georgia students to achieve the state’s academic standards, including additional resources and interventions for low-income students, those learning English, and students with disabilities. A new state funding formula that delivers the general curriculum for all students and the extra resources to address the needs of vulnerable student populations will provide the solid foundation required to build, sustain and support a qualified and stable teacher workforce across the state.

By moving to an opportunity weight funding mechanism, nearly all districts, and especially those with high concentrations of students experiencing household and/or neighborhood poverty, would have access to additional funds for programs and services that would bolster existing interventions. While new revenue would be required to properly fund the opportunity weight across the state, reallocating funds from the existing programs would reduce that amount considerably.

Acknowledgments

This report benefited from a thoughtful review by Stephen Owens, Senior Policy Analyst at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

This research was supported by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Endnotes

[1] While this boost will make teaching jobs more competitive, teacher salaries in Georgia lag well behind other professionals. Georgia ranked 46th out of the 50 states and Washington, D.C. in 2016 on wage competitiveness: teachers were found to earn 73% of what non-teachers of comparable age and with similar degrees earn.

[2] Hightower, A.M., Delgado, R.C., Lloyd, S.C., Wittenstein, R., Sellars, K., & Swanson, C.B. (2011). Improving student learning by supporting quality teaching: Key issues, effective strategies, Bethesda, MD: Editorial Projects in Education.

[3] National Center for Education Statistics. The Condition of Education: Public School Expenditures. (2019). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cmb.asp.

[4] Low-income status is measured through direct certification. Students are identified based on participation in other state assistance programs (SNAP, TANF, HeadStart, EvenStart) or based on student characteristics (homeless, migrant, foster or runaway).

[5] The student-teacher ratio in Georgia dropped from a ratio of 15.2 students to certified teachers in 2013 to 14.6 in 2019.

[6] Alternative certification here refers to teachers who do not yet meet Georgia teacher certification standards but are on a path towards certification. The most common forms of alternative certification for new teachers in Georgia school districts in 2019 were Induction Pathway 4 Teaching and Waivers: (Waivers and GaDOE Charter/SWSS Waivers).

[7] Darling-Hammond, L., & Haselkorn, D. (2009). Reforming teaching: Are we missing the boat? Education Week, pp. 30, 36; Darling-Hammond, L. (2000).Teacher Quality and Student Achievement: A Review of State Policy Evidence, Education Policy Analysis Archives 8(1): 32–3.

[8] Harris, D.N. & Sass, T. R. (2011). Teacher training, teacher quality and student achievement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7-8): 798-812.

[9] Borman, G.D. & Dowling, N.M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: A meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 78(3): 367-409.

[10] More specific details on teacher turnover estimates, the reasons behind the costs, and suggested steps to improve teacher stability can be found in the Learning Policy Institute’s “What’s the Cost of Teacher Turnover?” report.

[11] Loeb, S., & Page, M.E. (2000). Examining the link between teacher wages and student outcomes: The importance of alternative labor market opportunities and non-pecuniary variation. Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(3), pp. 393-408

[12] Borman, G.D. & Dowling, N.M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: A meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 78(3): 367-409.

[13] Kraft, M.A., Blazar, D., Hogan D. (2018). The Effect of Teacher Coaching on Instruction and Achievement: A Meta-Analysis of the Causal Evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4):547-588.

[14] Chingos, M., and Peterson, P. (2011). It’s easier to pick a good teacher than to train one: Familiar and new results on the correlates of teacher effectiveness. Economics of Education Review, 30: 449-465.

[15] Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1): 491–525.

[16] Hightower, A.M., Delgado, R.C., Lloyd, S.C., Wittenstein, R., Sellars, K., & Swanson, C.B. (2011). Improving student learning by supporting quality teaching: Key issues, effective strategies, Bethesda, MD: Editorial Projects in Education.