NEW JERSEY’S SCHOOL COUNSELOR CRUNCH

In the 2018-19 school year, 244,111 students in New Jersey did not have access to a school counselor, and at least 40% of all elementary schools had no school counselor on staff. In addition, the student-to-counselor ratio in the state’s poorest districts exceeded the standards set for all schools in the School Funding Reform Act (SFRA), according to an Education Law Center analysis of New Jersey Department of Education data.

The lack of counselors in many schools, along with excessive counselor caseloads, undermines the capacity of schools to address the myriad social, emotional and health impacts on students from the COVID-19 pandemic. The counselor shortage also is a serious barrier to implementing interventions to promote school safety and reduce the rate of suspensions, bullying, violence, and police involvement, since counselors are crucial to supporting restorative practices and other alternatives to harsh disciplinary action.

This report on school counselors follows a recent ELC report documenting a severe shortage of nurses in New Jersey schools, especially in the state’s poorest districts. Taken together, the two reports show how the Legislature’s chronic underfunding of the SFRA funding formula has resulted in serious shortages of vital support staff to serve vulnerable students and ensure their academic success.

In response to these reports, ELC is calling on the New Jersey Assembly and Senate Education Committees to investigate support staff shortages and their impact on students, especially in the poorest districts. Lawmakers must then work with Governor Phil Murphy and his Administration to ensure nurses and counselors are available to meet students’ social-emotional and educational needs, both during the pandemic and after the public health emergency subsides.

Counselor Caseloads

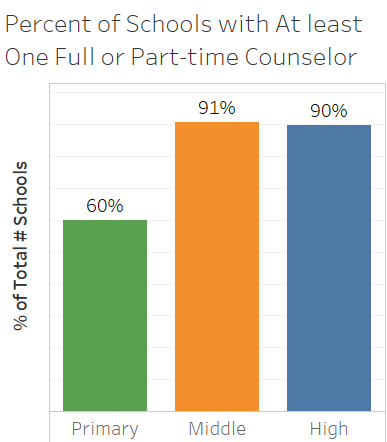

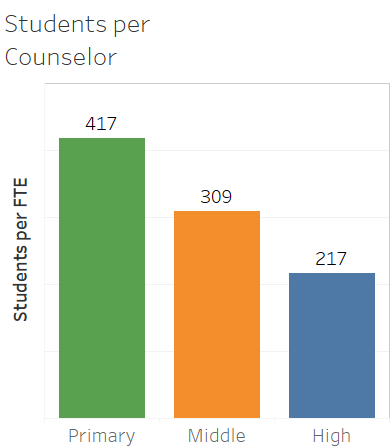

Nine out of every 10 New Jersey middle and high schools employ school counselors. Counselors are much less likely to be found at the elementary school level, in just six of every 10 schools. Among schools that have counseling staff, the student-to-counselor ratio is approximately 417 students per counselor in the primary grades, 309 students per counselor at the middle school level, and 217 students per counselor in high school.

These ratios are close to the school counselor staffing levels used in the SFRA formula. The SFRA establishes the following student-to-counselor ratios as adequate: one counselor for every 400 students in the primary school grades, one counselor for every 300 students in middle school, and one counselor for every 200 students in high school, with variations depending on the size of the district and the number of students enrolled.

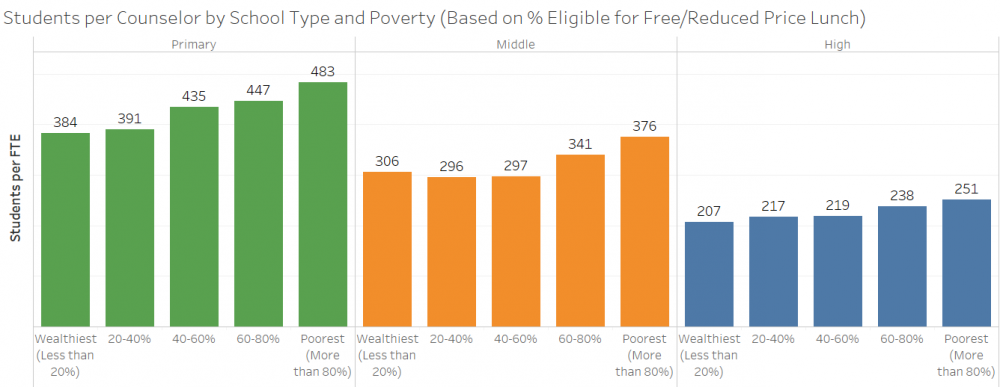

Schools in New Jersey’s poorer districts are slightly more likely than schools in wealthier districts to have at least one part-time or full-time counselor at the primary school level. But counselor caseloads are often much higher in poor districts at every grade level. This includes an average of 483 students per counselor at the primary level. In the upper grades, about 70 more students are assigned to middle school counselors in the poorest schools (376 students per counselor) compared to the wealthiest (306 students per counselor), and about 44 more students are assigned to a high school counselor in the poorest schools.[i]

The prevalence of a counselor shortage in higher poverty districts is not surprising given that these districts also have the largest funding gaps under the SFRA. The 593 schools in districts with a budget gap of $2,000 per pupil below the SFRA’s “adequacy” target have a student poverty rate of 69%, while the 864 schools in districts spending $2,000 per pupil above adequacy have a 14% poverty rate. Specific district-level breakdowns are available here.

Many schools in the highest poverty districts educate majority Black and/or Latino student populations. As a result, Black and Latino students often attend schools in which counselors shoulder higher caseloads than schools serving a predominantly white and Asian student population. This is particularly troubling given ELC’s analysis of NJDOE data on school discipline showing an alarming 9% of all Black students were suspended during the 2018-19 school year, compared to less than 3% of white students.

Counselors Play a Critical Role

Counselors have the essential role of supporting students during the pandemic and upon returning to school after potentially traumatic experiences, especially in districts segregated by poverty and race.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the need for counselors and nurses assigned to serve a manageable number of students in every school,” said Mary McKillip, ELC Senior Researcher. “But without the funding required by the SFRA formula, especially for those schools educating a majority of poor students and Black and Latino students, districts can’t provide enough counselors to serve every school at caseload levels mandated by the Legislature.”

“The need for school counselors has never been as acute as it is now in the pandemic, and that will be even more true when schools fully reopen,” said David Sciarra, ELC Executive Director. “Because counselors promote student well-being in multiple areas, from social-emotional health to anti-bullying and restorative justice initiatives, they are integral members of school staff. The Legislature must make providing a sufficient number of counselors to serve all students a top priority in the FY22 State Budget.”

[i]The wealthiest schools have less than 20% of students eligible for free or reduced price lunch, while the poorest schools have more than 80% percent eligible for free or reduced price lunch.

Press Contact:

Sharon Krengel

Policy and Outreach Director

skrengel@edlawcenter.org

973-624-1815, x 24

Press Contact:

Sharon Krengel

Director of Policy, Strategic Partnerships and Communications

skrengel@edlawcenter.org

973-624-1815, x240